The Touch Tour Dualities in Victor Vasarely’s Work

The 2024 ICOM CECA conference was held in Athens, Greece from 18-22 November. Delegates presented projects and research connected with the topic Delicate Issues – Challenging Audiences. CECA stands for Committee for Education and Cultural Action, which meant that most of the participants were education professionals or those doing research in that area. CECA is one of the largest committees in ICOM with approximately 2500 members. Emma Nardi, current President of the Executive Board of Directors of ICOM previously served as the president of CECA. During her opening remarks she stated her belief that museums are a platform for dialogue for sensitive issues, serve as a powerful force to inspire and that museum professionals have the ability to be agents of change in society. She called on all us to have the courage to change the world and make a difference together.

Marie-Clarté O'Neill the current president of CECA specifically expressed one request and one hope for the near future. She asked CECA members from all member countries to write the history of their activities and more generally, the history of museum education. Currently ICOM Hungary does not have a CECA Committee. This does not impede ICOM Hungary members from documenting their museum education work and the history of museum education in Hungary. Her hope, which many museum education professionals have expressed in the last couple of decades is that more museum educators will be invited to design galleries and curate exhibitions. ICOM Hungary would like to hear from you. When exhibitions are planned at the museum or heritage site where you work, to what extent are museum educators consulted and what role do they play in designing and curating exhibitions?

The opening speeches also included a very important message for those who feel that the place they work is too small to make any real impact. On the contrary, “Quality doesn’t depend on size, money or the type of collection. It depends on the genius of the educator.” The conference presentations presented below reflect this message – as museum educators explore topics connected with delicate issues, we challenge ourselves and the audiences we serve to build a more compassionate and just society.

Some museum educators are unsure of how to approach delicate subjects. Is it alright, for example, if visitors and staff leading the program feel “uncomfortable”? Sometimes that is the only way to feel. Dilemma games provide one way to approach sensitive issues and ethical questions. Dilemma games invite players to solve a series of challenges. Wencke Maderbacher, head of the Learning and Cultural Interaction Department at Moesgaard Museum in Denmark presented a dilemma game that was developed for the temporary exhibition Rus – Vikings in the East. It combined research and storytelling about Vikings. Television shows and films about Vikings abound, so we might think we know quite a bit about them. From these sources we have a picture in our minds of what they looked like and how they dressed. Maderbacker and her colleagues helped visitors understand that their picture of Vikings might be interwoven with some fiction. For example, we might be surprised to learn that Vikings purposely dressed to assimilate and blend in with the local community that they were passing through. That is – they dressed just like everyone else around them. Why? It allowed them to do a better trade. A better slave trade. In the dilemma game for Rus – Vikings in the East, visitors chose a character. As the game went on players realized that the characters who behaved the most recklessly scored the highest. The exhibition focused on the period from 800-1050 CE, when there were no “good guys” as slave trade was rampant in the world. Therefore, the museum felt they could not present a “feel good” tour because anyone really looking closely at the content of the exhibition would feel uncomfortable. If the collection or site you work at deals with delicate topics, Maderbacher offered dilemma games as one way to approach them with visitors. How do we make sure materials and approaches like dilemma games are tested with and used by the target population they were developed for?

When a museum decides to broaden its engagement network and plan programs and materials for specific target groups, museum educators often reach out to professionals in the community who work with them. In her talk, The Role of Key Informants when Working with Challenging Audiences in Museums, Carolina Silva from the University of Lisbon, Institute of Social Sciences in Portugal spoke about the roles these individuals play. Silva defined the term key informant as an individual who shares indispensable information about a target community. Museum educators’ knowledge and understanding of a group within their community increases by engaging in conversations with key informants. This then allows museum educators to plan better programs and materials. It may guide practical decisions connected with how programs are advertised, when the programs are held, and which types of refreshments are served as well as the content of program and the types of activities offered. Her work at Whitechapel Gallery in London led to the project Voices that Matter, community conversations about art. In England and throughout the United Kingdom organisations receive funding to run programs. Therefore, they are often documented and evaluated and the results are sent to the funding body. Silva indicated that often the layers of work are not seen in these reports, only the results. However, she underlined the importance of these layers for the museum educators, the key informant and the people who take part in the programs. Silva also noted that a key informants’ world view influences what information they share with museum educators. Their world view might benefit the program or act as a hinderance. Another double-edged sword museum educators sometimes run into is when they meet or contact gate keepers.

They may stand between the museum and potential visitors or inspire community member to participate. Silva found that gate keepers often act as mediators. They assess the setting for the participants. As both a researcher and a practitioner, Silva’s experience shows that it is not always clear at the onset who the “right” person is to contact to get access to the target community. The program YouthinMuseums aimed to increase the number of teenagers who visit art museums. It was a research project to get to know young people in a specific neighborhood and how to find gate keepers in order to get to know people in that local area. Her research showed that young people from different economic strata do not meet and talk to each other. She was surprised at how long it took her to find out who worked with youth at the municipality level. One reason is that often times professionals who work with a specific group of people in their community do not talk to each other. There is no network among professionals. Silva mentioned that teachers and schools also act as gate keepers. Therefore, it may take a while for the snowball effect to set it – to find the right person who opens the doors and helps museums engage with the target population in a meaningful way. Her research and experience showed that a community partner’s role can change through the course of the project, networking is ongoing an takes time, and a member of the team in a museum educators department needs to spend considerable time to foster and develop these networks. Therefore, she advises that when museum educators decide to broaden the scope of their engagement, they set clear and reachable objectives and ensure their and the partner’s expectations for the project are realistic.

How realistic is it for a museum educator like myself, who works with a collection largely based on visual perception to develop programs and materials for visually impaired visitors? This question has been asked by many who work at a heritage site or with objects that do not initially seem to lend themselves to this target group. Elena Santi’s and Isabella Colpo’s talk Everybody WellCAM! The long, holistic journey towards accessibility addressed their work with target populations who can or will not go to museums, live with visual impairment or developmental disorders. They work at the University of Padua, University Museum Centre (CAM) in Italy. They began their talk by describing what they looked like, which they feel provides an extra level of inclusivity for people living with visual impairment. I made a note to ask the visually impaired visitors I have been working with what aspects of my appearance they might be interested in. Santi and Colpo explained that people living with visual impairment usually do not go to new places, especially alone. Therefore, many are dependent on others – possibly key informants and gate keepers – just to get to the museum or heritage site. In much the way I have done over the past three years, Santi and Colpo explained that they tested materials with people living with visual impairment to assess how beneficial they were. The testers took on the role of key informants, providing essential information for museum practitioners. Santi and Colpo highly recommend asking target populations what needs they have and developing materials and activities based on their requests. The researchers methodological approach consisted of training themselves, meeting the target population and then repeating these two steps. Santi and Colpo suggest codesigning the experience with the target population to ensure that it is tailored specifically for them. When members of the target population are active participants, the project is more successful and reaches higher outcomes in a shorter period of time. They emphasized the slogan – Nothing about us without us. Although many people feel that only bigger museums have the resources to engage with target populations like the visually impaired, Santi and Colpo feel smaller museums are ideal for these types of projects because very often they have less traffic than larger venues. Museum educators from smaller museums might be raising their eyebrows and thinking – there is only one of me – how might I manage such an endeavor with everything else that is on my plate?

An inclusive approach might be the answer. After beginning to develop materials and activities to interpret the collection of works held at the Vasarely Museum Budapest for people living with visual impairment, I quickly realized that I could use them with all visitors. What had inspired me to begin? In 2022, the organisers of the Night of Objects specifically asked venues to offer programs for people living with disabilities. Having worked a bit with visually impaired people in the past, I dove in. The Touch Tour (which link to use – ask Tina) was born – access to the permanent collection through reproductions of works of art, sets of hands-on materials, gallery and art activities that visually impaired visitors may use to explore the permanent collection. This new direction also allows sighted visitors the opportunity to experience artworks by Victor Vasarely through their sense of touch and gives them a hint at what it might be like to live with severe visual impairment.

Victor Vasarely is often called the father of Op art as many of his artworks find their foundations in kinetic art and optical illusions. Viewing his pieces, thinking about them and discussing one’s experience with others allows visitors to have a better understanding of visual perception and how the brain processes visual stimuli. You might be asking yourself how something strongly connected with visual perception could be interpreted for visitors living with visual impairment. Although I have not come across anything Vasarely wrote regarding his use of optical illusions, he did incorporate one group of them, ambiguous images in many of his compositions. Since ambiguous images can be perceived in more than one way, a duality exists. This provided a place to begin – Vasarely’s works include all kinds of dualities – colours and shapes, math and art, movement and stillness, empty and full, convex and concave – the list just goes on and on. I put together some initial ideas and as Silva and Coplo recommend, tested them with people living with visual impairment. Based on their feedback, I got to work – first producing reproductions of reliefs in the collection, then hands-on interactives and finally materials for art activities.

After a bit of trial and error, I decided to make the sets of hands-on materials and reproductions of reliefs from Polyfoam. It is locally available, affordable and comes in dark grey and white, which provides a good contrast for people with some vision. In addition, I could cut polyfoam with the stencils I had, allowing me to make as many sets as I needed in-house. Having multiple copies has been very advantageous as it allows all of the participants to explore the same work of art at the same time.

By the time the Night of Objects event in 2023 came around I was ready. Before passing out the reproductions, I introduced Vasaely’s Plastic Alphabet. It is based on the interplay of two equal parts: shape and colour. His axiom 1=2, 2=1 means that one unit has two forms and two forms create one unit. The first units in his alphabet were squares which each contained another shape. In artworks like Beryl-Positive, we see that Vasarely placed either a shape or an empty frame on a square.

I invited sighted and visually impaired visitors to work in pairs. I also asked everyone to close their eyes and only use their sense of touch to explore a unit in Vasarely’s alphabet. Instead of giving pairs the same unit, I gave one person a square with another shape on it and the other person an empty frame which attached to a square. After silently exploring it, I asked the pairs to describe what they had to each other. They quickly realised that the frame and the shape were once together and they could put them back together by making something resembling a sandwich. Since then, I have used this set of hands-on materials with kindergarteners, elementary school students, teenagers, seniors, and people living with developmental disorders. All pairs do exactly the same thing, which shows that people’s curiosity is similarly sparked. This reinforced my belief that some concepts may be introduced to many target groups using the same materials. Although I have not read anything Vasarely wrote about his use of frames, he incorporated them into both collages and reliefs. His use of empty frames and the shape cut out of them allows us to speak about the contrast of empty and full, which also leads to a conversation about positive and negative space as well as background and foreground in an artwork.

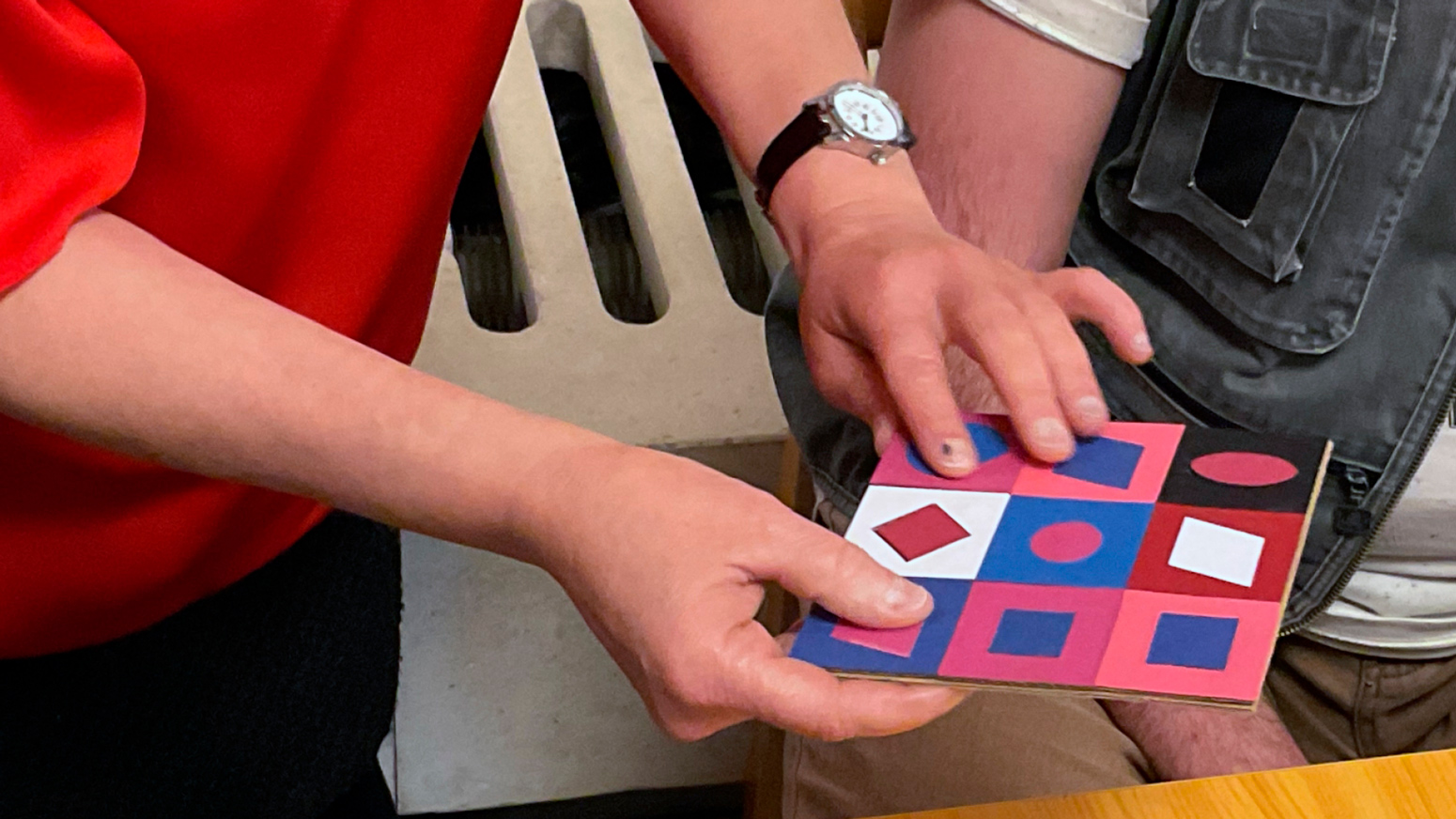

Before passing out reproductions of reliefs like Beryl-Positive, I asked several pairs to arrange their units in 3 x 3 compositions, where there are three units in each row with a total of nine units. After comparing and contrasting the two or three compositions the participants made, I collected the units and handed out the reproductions. Participants again worked in pairs and sighted visitors closed their eyes. The sets are magnetic and placed on ferromagnetic sheets so that they did not move around too much. I facilitated guided exploration of the composition by asking one member of each pair to place their hands gently on the reproduction and then I asked a question. Since they know that there are nine units from Vasarely’s alphabet in the composition, the first question I usually asked was how many units contained an empty frame and how many had a shape. They told their answer to their partner, took their hands off the reproduction and then their partner explored it by answering another question I posed. Four other artworks similar to Beryl-Positive are usually on display, therefore sometimes I passed out copies of one or more works of art. This required pairs to exclusively use their sense of touch to find the answers instead of listening to what other nearby participants said as the answers the question, “Which shape is in the middle?” would be different for each work of art.

After each pair felt they had a good idea of the composition, they could switch with other pairs and explored the second composition on their own, using the same process of exploring it through touch and sharing their findings with their partner. By comparing and contrasting the compositions, participants understand how Vasarely incorporated different aspects in each work. In Zaphir Positive the positioning of the triangles led to a discussion on movement, opposite directions as well as the rotational symmetry. If participants ran their finger around the four cut off edges of the four circles in Beryl-Positive, they understood that they make up a square. In that area of the composition, they find many dualities: frames and shapes, empty and full, round and straight lines, circles and squares, mathematics and art, as well as the philosophical idea of the sum and its parts.

My experience shows that partially and fully sighted visitors enjoy viewing the original reliefs. Therefore, we walked over to where they are on display. They found the ones they had explored and compared them to the others on the wall. Vasarely made each of these reliefs in pairs – the positive and negative version. Before a recent gift, there were no pairs in the collection. Now the museum displays one. The stencil I use cuts the shape out of its frame. Therefore, I am able to make the positive and negative version of each composition allowing visitors to explore works of art Vasarely made that are not in the museum’s collection.

The Vasarely Museum Budapest offers children, teenagers and adults interactive guided tours which include an art activity. Programs for people living with visual impairment have the same opportunity. After exploring works of art in the collection, they are offered similar materials to make their own compositions and I encourage them to incorporate aspects of dualities. The images below show coloured art materials. You might wonder why I produced them in such a range of colours. Some people with visual impairment perceive colours and some who have lost their vision remember them. While working and after finishing, just like sighted people, participants living with visual impairment eagerly explore other participants’ compositions. Those who have returned over the last three years reported that they took out what they made on their last visit to refresh their memory before returning to the museum for the next program.

While some participants do perceive colours, many asked if I would develop a set of materials for those who do not perceive colours well. I began with the work Caribe Positive because I have been told that black and white provide the largest visual contrast. My question was, “Which textures provide the largest contrast?” Not wanting there to be just one answer to the question, I chose materials where each participant would come up with their own conclusion based on subjective reasoning. I paired one texture with each of the seven spectrum colours. After following a similar process as outlined above, participants also felt each texture, identified the type of material it was (cardboard, felt, foam, self-adhesive stickers) and then chose two textures that they felt provided the largest contrast. After sharing their ideas, they used those textured materials to create compositions with a focus on contrast.

What other aspects can I focus on? The more I work with visually impaired visitors, the more inclusive strategies I find. I have begun to review all the materials I have made so far and see which ones I to try out with visually impaired visitors. When planning the Saturday Sleuth workshops, my goal is to make them as accessible as possible. By attending the 2024 ICOM CECA conference Delicate Issues – Challenging Audiences, I learned about how museum educators around the world face the same struggles and what solutions and strategies they have come up with. Combining them with my own vision of inclusive museum education helps me move forward and open the door to more visitors.

ICOM Hungary supported my participation in the conference.

Litza Juhász